'A mesmerising mirage': How Monet's paintings changed the way we see London

Published 3:26 PM Oct. 21, 2024

A new exhibition charts how Claude Monet's revolutionary, fog-shrouded visions of the Thames would "irreversibly alter how London saw itself".

A new exhibition charts how Claude Monet's revolutionary, fog-shrouded visions of the Thames would "irreversibly alter how London saw itself".

Some artists help us perceive the world more precisely. A rare few go further. They look beyond looking. Theirs is a deeper reality, more felt than seen. Claude Monet is one of those. In three visits to London between 1899 and 1901, the French Impressionist, then approaching 60 years of age, embarked upon one of the most ambitious series of penetrating paintings ever undertaken by any artist – a project that is now the focus of a groundbreaking exhibition at the Courtauld Institute, Monet and London: Views of the Thames.

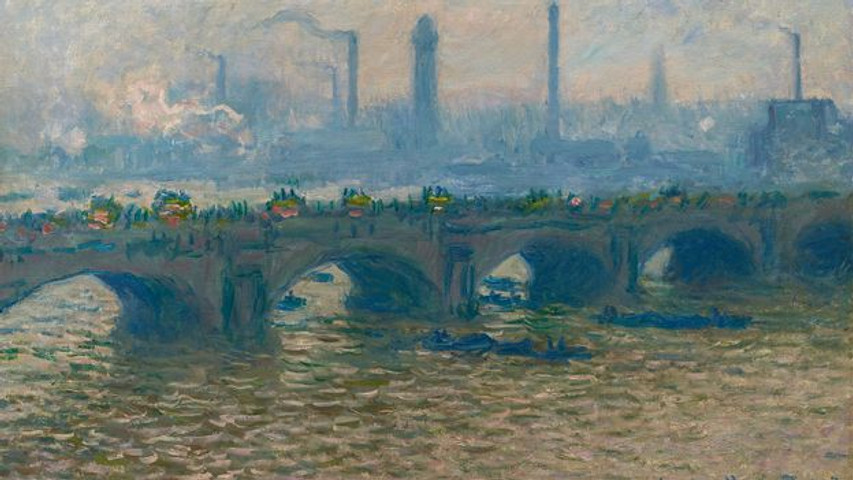

From a murky miasma of toxic, soot-laced smog that choked the very breath of the Thames, Monet magicked up nearly 100 paintings – more than he would devote to any other subject in his long career. His evanescent visions, which dissolve the heft of London's crowded bridges and imposing palaces into intangible tapestries of vibrating vapour, would shape forever the way the world conceived of the "unreal city", as TS Eliot would later call it – a place beyond place that sits outside of time, an ethereal elsewhere.

What Monet was really compiling weren't studies of a city but experiments in optics – a pioneering treatise on the undiscovered properties of light itself

Consider the evaporative power of a single instalment of the sprawling series, London, The Houses of Parliament, Shaft of Sunlight in the Fog. Among the best known of Monet's views of the Thames, the painting captures the propulsive turrets of the Palace of Westminster, juddering in a flash of late-afternoon sun that teasingly transparentises a curtain of fog that shrouds the neo-Gothic structure.

During the artist's second stay in London in 1901, Monet began chronicling the fluctuating temperaments of the Houses of Parliament from a covered terrace of the recently constructed St Thomas's Hospital, directly across the river from the palace on the Southbank. A year earlier, the artist had begun translating, from the balcony of his sixth-floor rooms in the Savoy Hotel where the series began in September 1899, the shifting dispositions of dawn light as it alchemised the rigid reach of Waterloo Bridge and Charing Cross Bridge into luminous levitations. The ensuing studies of the Houses of Parliament, caught at different times of the day and in varying densities of smog and mist, demonstrate a further intensification of the artist's understanding of the very essence of his subject.

Published 3:26 PM Oct. 21, 2024

A new exhibition charts how Claude Monet's revolutionary, fog-shrouded visions of the Thames would "irreversibly alter how London saw itself".

A new exhibition charts how Claude Monet's revolutionary, fog-shrouded visions of the Thames would "irreversibly alter how London saw itself".

Some artists help us perceive the world more precisely. A rare few go further. They look beyond looking. Theirs is a deeper reality, more felt than seen. Claude Monet is one of those. In three visits to London between 1899 and 1901, the French Impressionist, then approaching 60 years of age, embarked upon one of the most ambitious series of penetrating paintings ever undertaken by any artist – a project that is now the focus of a groundbreaking exhibition at the Courtauld Institute, Monet and London: Views of the Thames.

From a murky miasma of toxic, soot-laced smog that choked the very breath of the Thames, Monet magicked up nearly 100 paintings – more than he would devote to any other subject in his long career. His evanescent visions, which dissolve the heft of London's crowded bridges and imposing palaces into intangible tapestries of vibrating vapour, would shape forever the way the world conceived of the "unreal city", as TS Eliot would later call it – a place beyond place that sits outside of time, an ethereal elsewhere.

What Monet was really compiling weren't studies of a city but experiments in optics – a pioneering treatise on the undiscovered properties of light itself

Consider the evaporative power of a single instalment of the sprawling series, London, The Houses of Parliament, Shaft of Sunlight in the Fog. Among the best known of Monet's views of the Thames, the painting captures the propulsive turrets of the Palace of Westminster, juddering in a flash of late-afternoon sun that teasingly transparentises a curtain of fog that shrouds the neo-Gothic structure.

During the artist's second stay in London in 1901, Monet began chronicling the fluctuating temperaments of the Houses of Parliament from a covered terrace of the recently constructed St Thomas's Hospital, directly across the river from the palace on the Southbank. A year earlier, the artist had begun translating, from the balcony of his sixth-floor rooms in the Savoy Hotel where the series began in September 1899, the shifting dispositions of dawn light as it alchemised the rigid reach of Waterloo Bridge and Charing Cross Bridge into luminous levitations. The ensuing studies of the Houses of Parliament, caught at different times of the day and in varying densities of smog and mist, demonstrate a further intensification of the artist's understanding of the very essence of his subject.

Published 3:26 PM Oct. 21, 2024

A new exhibition charts how Claude Monet's revolutionary, fog-shrouded visions of the Thames would "irreversibly alter how London saw itself".

A new exhibition charts how Claude Monet's revolutionary, fog-shrouded visions of the Thames would "irreversibly alter how London saw itself".

Some artists help us perceive the world more precisely. A rare few go further. They look beyond looking. Theirs is a deeper reality, more felt than seen. Claude Monet is one of those. In three visits to London between 1899 and 1901, the French Impressionist, then approaching 60 years of age, embarked upon one of the most ambitious series of penetrating paintings ever undertaken by any artist – a project that is now the focus of a groundbreaking exhibition at the Courtauld Institute, Monet and London: Views of the Thames.

From a murky miasma of toxic, soot-laced smog that choked the very breath of the Thames, Monet magicked up nearly 100 paintings – more than he would devote to any other subject in his long career. His evanescent visions, which dissolve the heft of London's crowded bridges and imposing palaces into intangible tapestries of vibrating vapour, would shape forever the way the world conceived of the "unreal city", as TS Eliot would later call it – a place beyond place that sits outside of time, an ethereal elsewhere.

What Monet was really compiling weren't studies of a city but experiments in optics – a pioneering treatise on the undiscovered properties of light itself

Consider the evaporative power of a single instalment of the sprawling series, London, The Houses of Parliament, Shaft of Sunlight in the Fog. Among the best known of Monet's views of the Thames, the painting captures the propulsive turrets of the Palace of Westminster, juddering in a flash of late-afternoon sun that teasingly transparentises a curtain of fog that shrouds the neo-Gothic structure.

During the artist's second stay in London in 1901, Monet began chronicling the fluctuating temperaments of the Houses of Parliament from a covered terrace of the recently constructed St Thomas's Hospital, directly across the river from the palace on the Southbank. A year earlier, the artist had begun translating, from the balcony of his sixth-floor rooms in the Savoy Hotel where the series began in September 1899, the shifting dispositions of dawn light as it alchemised the rigid reach of Waterloo Bridge and Charing Cross Bridge into luminous levitations. The ensuing studies of the Houses of Parliament, caught at different times of the day and in varying densities of smog and mist, demonstrate a further intensification of the artist's understanding of the very essence of his subject.

Published 3:26 PM Oct. 21, 2024

A new exhibition charts how Claude Monet's revolutionary, fog-shrouded visions of the Thames would "irreversibly alter how London saw itself".

A new exhibition charts how Claude Monet's revolutionary, fog-shrouded visions of the Thames would "irreversibly alter how London saw itself".

Some artists help us perceive the world more precisely. A rare few go further. They look beyond looking. Theirs is a deeper reality, more felt than seen. Claude Monet is one of those. In three visits to London between 1899 and 1901, the French Impressionist, then approaching 60 years of age, embarked upon one of the most ambitious series of penetrating paintings ever undertaken by any artist – a project that is now the focus of a groundbreaking exhibition at the Courtauld Institute, Monet and London: Views of the Thames.

From a murky miasma of toxic, soot-laced smog that choked the very breath of the Thames, Monet magicked up nearly 100 paintings – more than he would devote to any other subject in his long career. His evanescent visions, which dissolve the heft of London's crowded bridges and imposing palaces into intangible tapestries of vibrating vapour, would shape forever the way the world conceived of the "unreal city", as TS Eliot would later call it – a place beyond place that sits outside of time, an ethereal elsewhere.

What Monet was really compiling weren't studies of a city but experiments in optics – a pioneering treatise on the undiscovered properties of light itself

Consider the evaporative power of a single instalment of the sprawling series, London, The Houses of Parliament, Shaft of Sunlight in the Fog. Among the best known of Monet's views of the Thames, the painting captures the propulsive turrets of the Palace of Westminster, juddering in a flash of late-afternoon sun that teasingly transparentises a curtain of fog that shrouds the neo-Gothic structure.

During the artist's second stay in London in 1901, Monet began chronicling the fluctuating temperaments of the Houses of Parliament from a covered terrace of the recently constructed St Thomas's Hospital, directly across the river from the palace on the Southbank. A year earlier, the artist had begun translating, from the balcony of his sixth-floor rooms in the Savoy Hotel where the series began in September 1899, the shifting dispositions of dawn light as it alchemised the rigid reach of Waterloo Bridge and Charing Cross Bridge into luminous levitations. The ensuing studies of the Houses of Parliament, caught at different times of the day and in varying densities of smog and mist, demonstrate a further intensification of the artist's understanding of the very essence of his subject.